New publication: research on how the microbiome of the nost and throat change as we age

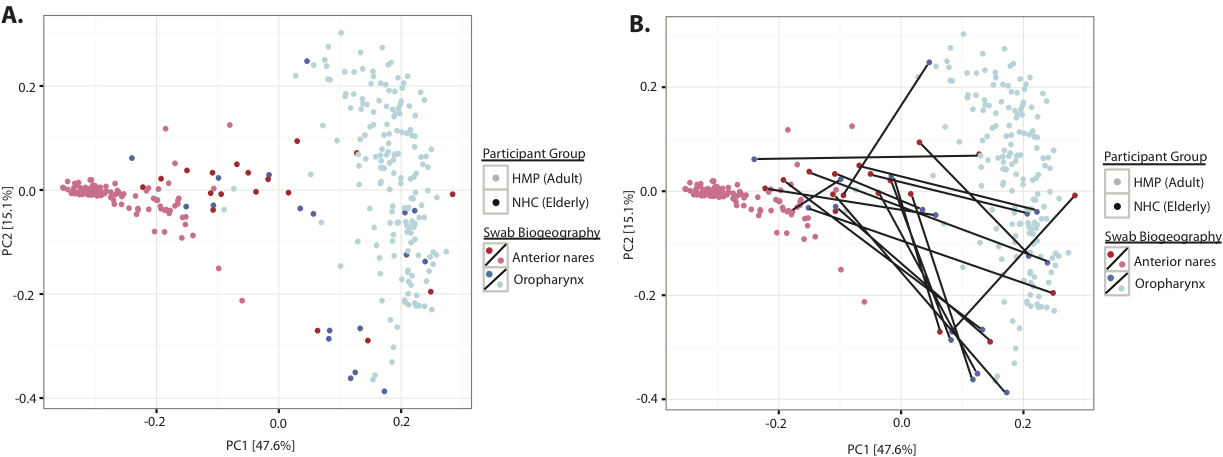

A recent article in the Annals of the American Thoracic Society is the result of an extensive collaboration between the Bowdish and Surette labs (colloquially referred to as the “Bowdettes”) on a study of the upper respiratory tract microbiomes. As we age, we become more susceptible to respiratory infections such as influenza and pneumonia; however, we aren’t yet sure why. The microbial communities, or microbiomes, that inhabit our noses and throats act as protectors of our respiratory tract from microbes in our environment. Previous research has identified that immune function declines with age, but an understanding of whether this is correlated with changes to the respiratory tract microbiomes remained unknown. In this study, we rectified this by collecting swabs of the anterior nares (nostril) and oropharynx (throat) from willing elderly volunteers, and profiled these microbial communities using 16S rRNA sequencing of the variable 3 region. Initial analyses of these data indicated that there were no associations of these microbiomes with gender, the residence of the participant, or other factors. Interestingly, the microbiota sampled from the noses and throats of these individuals did not look distinct from each other, meaning that the microbes found in these participants noses were similar in type and number to those found in their throats. In fact, when we combined this data with that of healthy, mid-aged adults sampled at the same locales as part of the Human Microbiome Project, we discovered that the microbiota of the elderly were very different from that of adults, and included more variability among subjects. Interestingly, we did not discover an increase in the abundance of any pathogenic species such as Streptococcus pneumoniae which often cause respiratory infections. These results are important as we consider the implications to the study of respiratory infections. We can hypothesize that the dysbiosis if the microbial communities of the upper respiratory tract with age may affect immune function, or the effectiveness of these ecological barriers, allowing pathogens such as S. pneumoniae to easily infiltrate; however, further research will have to be conducted in order to fully examine the effect these microbial changes will have on us as we age. Our paper can be found here; if you have any questions or comments, please leave us a note below or on the Surette lab website!